Hello David

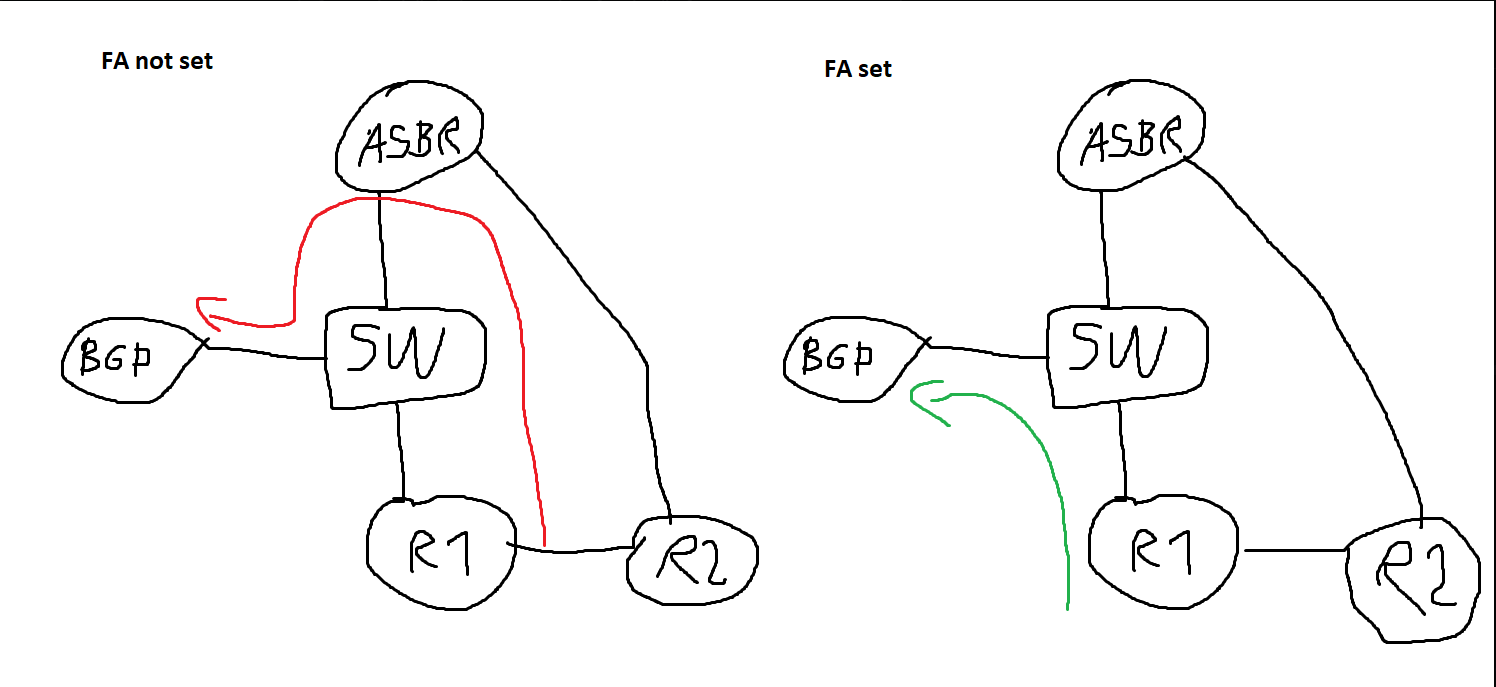

The diagrams you have shared describe this feature very well. In this scenario, your ASBR has an adjacency with R2, and is also connected to the BGP router. It learns about routes that originate outside of the OSPF domain from the BGP router, and this makes it an ASBR.

By default, the FA is set to 0.0.0.0. A condition for the ASBR sending a non-zero value is that the interface facing the BGP router should have OSPF enabled and should not be passive. Why?

First of all, by enabling OSPF on that interface, you can guarantee that ALL other OSPF routers can reach that address (the subnet of that interface) using OSPF internal routes.

When another router (like R1 in your diagram) receives a Type-5 LSA with a non-zero FA, it must perform a recursive route lookup to resolve that FA. According to RFC 2328, the FA must be reachable via an OSPF intra-area or inter-area route (Type-1, Type-2, or Type-3 LSA).

If OSPF is not enabled on that interface, you can have suboptimal routing or a black hole! Specifically, let’s say the the ASBR sets FA to the external next-hop IP (e.g., 10.0.12.5). R1 receives the Type-5 LSA and attempts to look up 10.0.12.5. R1 finds no OSPF internal route to 10.0.12.0/24 (because it’s not in the LSDB). R1 either discards the route as unreachable or cannot properly calculate the path.

But with OSPF enabled, the ASBR’s OSPF process advertises 10.0.12.0/24 as an internal OSPF subnet (via Type-1/Type-2 LSA). All OSPF routers know how to reach 10.0.12.0/24 via SPF calculation. When they receive the Type-5 with FA=10.0.12.5, they can properly resolve it, resulting in optimal routing directly to the FA.

Now keep in mind that you’re NOT running OSPF “into the external domain.” The interface is OSPF-enabled because that particular IP subnet needs to be part of the OSPF topology so the FA, which is in the same subnet, is reachable. The segment connects to an external next-hop AND provides an OSPF transit path.

Now why does it have to be NOT passive? Well, in OSPF, passive interface advertises the connected subnet as a stub network (a dead-end) in the Type-1 Router LSA. It does not participate in normal OSPF transit behavior, so there are no hellos, no adjacencies, no DR/BDR election. But the whole point of a non-zero FA is that that segment acts as a transit path. So marking it as passive tells OSPF it’s not a transit path, so the network to which the FA belongs may be reachable, but is considered unusable as a next hop to get to a network beyond that.

So to summarize: Even though the passive interface restriction doesn’t explicitly require an adjacency to form (there will typically be no OSPF neighbor on that segment), the interface must be capable of normal OSPF operation (hello processing, network type advertisement) to qualify as a legitimate transit segment for FA purposes.

It does feel unusual, but hopefully it has become a little more intuitive with this explanation. I haven’t seen this implementation in practice in a production network. However, it does make sense to provide this capability, especially in provider networks where efficiency is of utmost importance.

I hope this has been helpful!

Laz

![]() It feels… unusual

It feels… unusual